Back in 2011, researchers from The University of Chicago and Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History (including Dr. Josh Drew and Dr. Mark Westneat), mounted an expedition to Papua New Guinea (PNG). Their primary goal was to quantify the diversity of fishes in Bootless Bay, a shallow harbor adjacent to the country's capital of Port Moresby.

Ultimately, their research suggests that 949 fish species are present in the Bootless Bay area. Compared to other sites in PNG, this bay is relatively species-poor. Although limited sampling effort may skew the diversity estimates somewhat, anthropogenic factors (proximity to a major population center, habitat degradation, and exploitation) likely contribute to the low diversity estimates in this area. (See: Drew et al. BMC Ecology 2012, 12:15)

This summer, the majority of Hawkmoth posts have focused on fieldwork. The expedition to Fiji had similar goals to those in PNG. Both trips were intended to quantify reef fish diversity in areas subject to anthropogenic pressures, and both studies are relevant to questions on a much larger geographic scale, concerning broad patterns of diversity across the tropical Indo-Pacific.

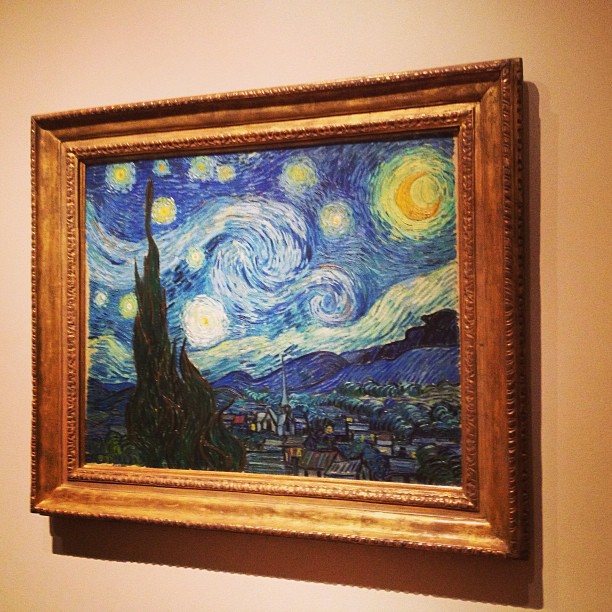

Geographically, Fiji sits on the periperhery of a region known as the Coral Triangle (outlined in the photo above, with Fiji identified to the east). Bounded by Indonesia, The Phillipines, and Papua New Guinea, the Coral Triangle is the heart of earth's marine biodiversity. This relatively small area boasts 50% of the planet's coral reefs (see: Coral Triangle Initiative).

What we see is a steep drop in biodiversity from areas within the Coral Triangle to those on the periphery. Reefs in Indonesia and New Guinea have many more fish species than those in Fiji. But how did that happen? By quantifying the diversity of fishes in and around the Coral Triangle, we begin to trace the gradient of change in biodiversity here. Ultimately, this will help illuminate the how and why of reef community composition in the most diverse marine systems on earth.